The federal government created the formula to calculate eligibility for Pell grants in 1972. A lot has changed in higher education since then, but this formula has “barely budged.” At the same time, the Pell Grant has not kept up with the rising price of college. In 1980, a student receiving maximum Pell could cover nearly 100 percent of the cost of a 2-year college and nearly 80 percent of the cost of attendance of a 4-year public college. Today, the maximum Pell only covers less than 30 percent of a four-year college cost of attendance. As the purchasing power of the Pell Grant declines, and more students reach for a postsecondary credential, Congress faces important questions about how complicated the federal aid formula is, and who benefits most from it as it is currently set up.

Not only is the maximum Pell Grant not enough, but the formula used to distribute these funds, or the Expected Family Contribution (EFC), is also in desperate need of an update. This creates a dual problem for some students: receiving an EFC larger than $0 means that college is not realistically affordable because their family cannot pay, yet $0 EFC may not produce enough aid to afford college anyway.

What is Expected Family Contribution?

After filling out the FAFSA, students receive their Student Aid Report which lists, among other things, their Expected Family Contribution (EFC), or the amount of money the government expects the student to pay out-of-pocket for college. Federal EFC is calculated using a family’s income, assets, and benefits, as well as family size and number of family members in college. There are three federal EFC formulas – one for dependent students, one for independent students without dependents other than a spouse, and one for independent students with dependents other than a spouse. Dependent students and independent students with dependents who make less than $25,000 per year automatically receive a zero EFC, which qualifies them for the maximum Pell grant award.

Schools subtract the EFC from their cost of attendance to calculate total need. Based upon need and other requirements, students may be eligible for Federal Pell Grants, direct loans, and federal work-study. Need-based aid, however, may not cover the total need. In these instances, schools fill the gap with loans – direct unsubsidized, federal PLUS, and private.

Why do we need to change the EFC formula?

Zero EFC Does Not Reflect the Reality of a Family’s Financial Situation

For many students, it is not just a question of which school they wish to attend, but also which school they can afford to attend. Every year, students open their Student Aid Report, and are shocked to see their Expected Family Contribution. They know that their family simply can not afford to pay that amount of money, right there in black and white. Students like Alyssa, whose parents take care of her four siblings and sick grandmother, yet are expected to contribute money each year for her college education. Or McKael, whose mother postponed her wedding so that McKael’s EFC would not shoot up with the added income from a new step-parent who may not feel obligated to pay for school. For other students, they must choose between working while attending school or taking private loans to make up the difference. Some might even postpone their education plans altogether.

Zero EFC Prevents Colleges from Targeting the Neediest Students

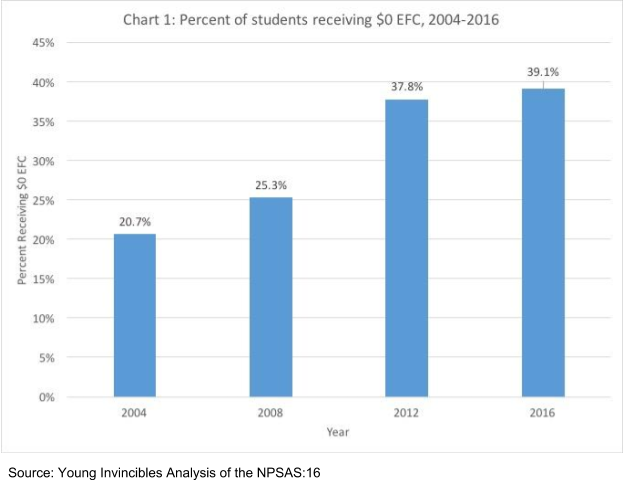

EFC is also too blunt an instrument to calculate need. Nearly 40 percent of students received a $0 EFC in 2016, and that number is growing. In fact, between 2004 and 2016, the percent of students with zero EFC nearly doubled (Chart 1). As more students qualify for $0 EFC, it becomes harder for the neediest students to receive the aid they require. For example, a family income of $10,000 automatically receives the same EFC as a family income of $20,000, despite their incomes differing by a factor of two. While both families face major barriers to paying for college, the family with higher income may have more to contribute to their education and to cover non-college related expenses which are essential to college success for some students, such as childcare. Their choices may not be as limited as the lower income family.

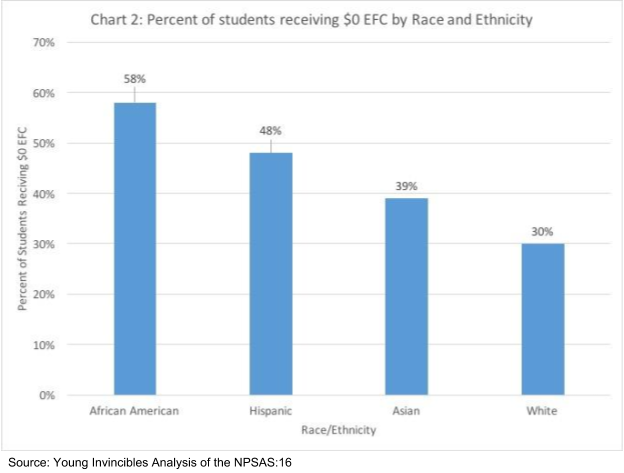

This is particularly important for students of color, who represent a greater portion of $0 EFC recipients (Chart 2) and are also more likely to be independent students with dependents. It is also particularly important for African American students, because they take out, on average, more money in total loans than white students and are more likely to withdraw from college without receiving a credential. These students are also more likely than white students to be forced to default on their loans or be delinquent in payment.

How do we fix it? – Raise the Maximum Pell Grant, Allow for Negative EFC, and Increase the Threshold for Automatic Zero EFC

Increasing the maximum amount of money available through the Pell Grant should be Congress’s first priority for tackling college affordability. The Aim Higher Act, introduced in the last Congress, proposes increasing the maximum Pell Grant award by $500. This is a good start, but there is room for bolder and more comprehensive solutions.

From there, the EFC formula could be changed to allow for negative EFC. This can be accomplished by changing the formula to account for debt and regional cost of living, all of which have a profound effect on the amount of money a family can contribute to the cost of college. Current FAFSA data allows for the calculation of negative EFC, which would allow schools to target their financial aid to their neediest students. This change must be accompanied by an increase in the maximum Pell award, so as not to inadvertently take money from students who receive $0 or greater EFC.

Proposals for negative EFC date back to at least 1991, and Senator Edward Kennedy introduced the Strengthening Student Aid for All Act, a negative EFC bill, in 2008. Current proposals call for a negative EFC limit of $750, which provide up to an additional $750 in Pell Grant assistance. It may not seem like much, but research shows that even modest increases to the Pell Grant award will “significantly help improve attendance and completion” for underserved students.

Further, Congress can increase the threshold for automatic zero EFC, which allows low-income students to qualify for $0 EFC while submitting minimal information about income and assets. Until 2012, students with an adjusted gross income of $32,000 or lower received an automatic zero EFC. In 2012, Congress lowered the automatic zero EFC threshold by $9,000 to $23,000. This change put another financial burden on low-income students who may qualify for zero EFC anyway. These students are overwhelmingly students of color. Congress should, at a minimum, increase the automatic zero EFC threshold back to its pre-2012 level of $32,000 (or $35,000 if adjusted for inflation).

Conclusion

The EFC formula does not reflect the reality facing today’s students and families. For many students, anything other than $0 EFC is not realistically affordable, and for some students, a $0 EFC does not produce enough aid to afford college anyway. This is why Young Invincibles will continue to advocate for students and encourage Congress to raise the maximum Pell Grant award and make substantive changes to the EFC formula. Students can join the conversation by reaching out to their member of Congress and sharing their stories.

Authored by Greg Hirschfeld