Young adults may not be the first people that come to mind when talking about Medicaid, the government health program that provides health coverage to folks living at or near the poverty line. That’s a problem, because what most people don’t realize is that under new Medicaid restrictions advancing in several states, a disproportionate number of young people could lose their access to health care.

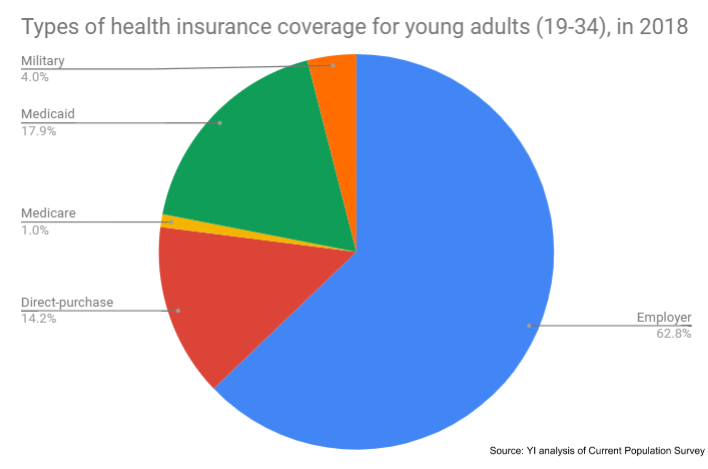

Young adults face dire economic challenges today — lower salaries than their parents, skyrocketing student loan debt, and underemployment. The challenges are even greater for young people of color. Young African Americans, for example, have lost ground financially, with median net wealth declining nearly by half since 1989. So for the 12.3 million people between the ages of 19-34 with Medicaid coverage, this program is the difference between getting basic health care and going without. Nationwide, young adults make up of 20 percent of all Medicaid recipients.

Yet some states are threatening to take away this needed Medicaid coverage by imposing unnecessary requirements that adults prove, often through complicated paperwork, that they work, or participate in work-related activities, for a minimum number of hours in order to maintain health coverage through Medicaid.

Who is likely to lose coverage under these burdensome and confusing new rules? Young adults who are already struggling to pay their bills and put food on the table — many of whom are doing so while holding down at least one job, going to school, or caring for family members.

In Kentucky, for example, a Young Invincibles analysis finds that young adults (ages 19-34) are nearly twice as likely to be impacted by work requirements as all Medicaid enrollees. Over 40,000 young Kentuckians could lose coverage if these work requirements — which are currently blocked in court — take effect.

Why? One factor is underemployment. We know that many young Americans take on multiple jobs where they can get them, including jobs outside their expertise, simply to pay the bills. The problem is, many of these jobs (think: waiting tables, retail, bartending, Uber driving, and other kinds of work in the gig economy) have irregular hours that can vary week-to-week. If their health coverage suddenly required proof of a minimum of 20 hours per week, every single week, these young adults could very quickly lose the coverage on which they depend. That’s true in Kentucky, where about half of the young adults who might lose their Medicaid coverage already work, but may not always work the hours necessary to keep their coverage.

Another factor is the reporting burden placed on young people as they balance work, school, and family obligations. On top of doing their actual work, these young adults will need to gather, provide, and submit proof of the hours they worked each month. If the Medicaid reporting process in Kentucky will be anything like it is in Arkansas, many young Kentuckians will lose their health care because of unreliable internet access, the only method to report hours worked. More than half of the young Kentuckians at risk of losing Medicaid coverage do not have high-speed internet in their homes, which means they’d need to spend hours at a local library or other public location filling out the required forms — assuming that they even have accessible transportation to get there.

These policies will hurt those who already face some of the highest barriers to care. For example, our analysis shows that African Americans make up 10 percent of the young adult population in Kentucky, but account for 14 percent of the young adults who could lose Medicaid coverage. For many systemic and structural reasons, black Kentuckians are already uninsured at a higher rate than white Kentuckians, and adding work requirements would only deepen health care inequality for black communities.

It is important to understand that these young adults have nowhere else to turn for health coverage. To even qualify for Medicaid, a single person must make less than $17,000 a year. For a young adult living in Louisville, Kentucky, that’s less than half of what they need to afford modest annual living expenses such as housing, food, transportation, and taxes. There’s just not a lot leftover to pay for additional insurance premiums once Medicaid is taken away.

Proponents of Medicaid work requirements claim these new restrictions will save taxpayers money, but the truth is, they’ll do the opposite. Estimates show that the extra burden of reporting and certifying hours worked costs millions of dollars to the states, reducing any savings gained by reducing beneficiaries. For instance, Virginia’s Department of Medical Assistance Services estimates setting up the system will cost $3.5 million and eventually cost $7.7 million to operate. Another government estimate puts the price tag as high as $23.1 million per year. Studies suggest work requirements don’t even increase employment in the long run.

So as debate over work requirements continues, just remember — this has real consequences for young people. We’re looking at the potential for thousands of young people getting kicked off of their coverage, for unnecessary requirements, and for burdensome reporting. If we want young people, who are the future of our economy, to be able to work and afford health care, we should be talking about meaningful policy changes, not a solution in search of a problem like work requirements.