Numerous studies have demonstrated how labor market outcomes information can influence student perspectives and decisions on where to got to college and what to study. A new study from the Urban Institute suggests such information fails to influence prospective high school students’ decisions, specifically on what institutions to enroll and majors to declare. The researchers’ three-year experiment relies on a search tool developed especially for the study, and creatively blends numerous data sources, including the Virginia Longitudinal Data System, a powerhouse network connecting individual-level, education and workforce data in the Commonwealth.

However, the study suffers from numerous methodological flaws, including poor design of the tool itself that led to very low use by students. Policymakers and educators should hesitate from interpreting the results as evidence that good information and well-designed tools don’t and can’t improve college decisions. This blog organizes our critiques into two categories: design flaws of the tool that was supposed to deliver the information, and assumptions and baselines made in their effect comparisons.

The researchers made a bad tool and students didn’t use it

The tool the study relies on to deliver the outcomes information to students failed to actually deliver the information. Few students actually used the tool, and we shouldn’t be surprised by this given its design and functionality.

Rolling out new tools is always hard

To test whether high school students would be influenced by different types of information, the researchers actually built their own college search tool called GradpathVA. This is red flag number one, as there are already dozens of college search tools already out there competing for attention from families, students, and counselors (U.S. Department of Education’s College Scorecard, College Board’s Big Future, etc.). While the study attempted to help counselors promote the tool with flyers and seminars, it’s an uphill battle to earn buy-in from students to actually use a new tool.

The researchers acknowledge that “[U]sage of the GradpathVA site was low.” Out of 300 high schools contacted, only 25 participated in the study. For schools that did participate, the tool only received an average 21 visits per high school, throughout the entire year (p. 19). And those visitors could have been from counselors the researchers were trying to convince to adopt the tool.

If students aren’t using the tool, it’s misleading to claim the information in it isn’t effective. That’s like measuring the safety of seat belts in cars, but only taking into account whether the car had seat belts installed, not if passengers are actually using them. Or comparing weight loss between people who were sent exercise videos, not who actually exercised. We’re very sympathetic to the difficulty of capturing users for a new tool, but the fact that students didn’t use this tool isn’t evidence that information can’t improve decision-making.

Design Matters

Two reasons the researchers probably struggled with buy-in from students is the tool itself isn’t exactly intuitive to use or aesthetically pleasing (good design and usage often correlate). The federal government has actually pulled together a lot of design principles this tool could benefit from, like using contrasts, white space, graphic focal points, and other techniques to allow the text to breath and improve usability.

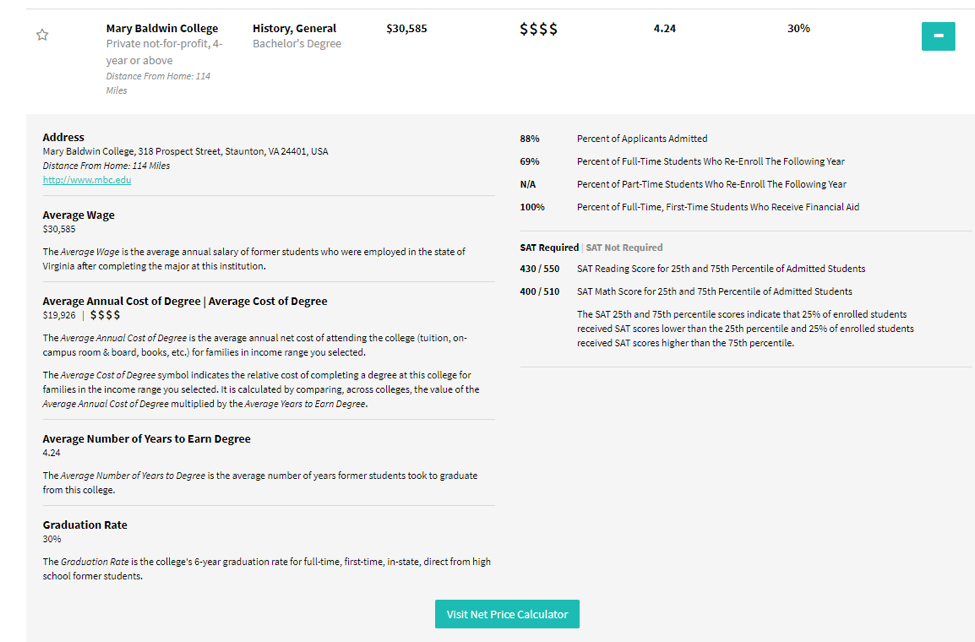

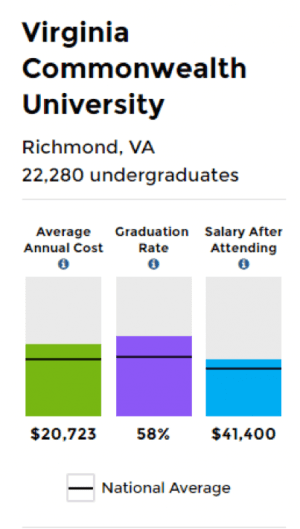

The dimensions of the landing page don’t draw the user to the boxes for to input the relevant information, potentially confusing the user on what to do next. Once the user selects a college and program, the information pretty much exclusively is conveyed via text. This is exhausting to the user and causes the eyes to glaze over. Compare that to the College Scorecard tool which visualizes the data and benchmarks against the national average. I can’t imagine students being drawn to visit and re-visit this tool.

We’ve learned at Young Invincibles how important it is to personally tailor information to improve cognition and recall. Our own app we built for the California Community Colleges, Here to Career, starts with an interests quiz assessing what skills and activities students are interested in, and then produces a customized list of occupations that align with their interests.

GradPathVA’s customization is limited, asking the user only what subjects they are interested in, their family income, and zip code and produces results based on those inputs. Compare that to the College Scorecard, which allows users to search by size of the school, specialized mission, and of course name of the institution. Or compare this limited customization to College Measures’ “Launch My Career” series, that allows users to select what job skills they might be interested in pursuing and then connecting them to relevant programs.

Mobile

We also know today’s young adults disproportionately rely on mobile devices for their internet access: 92 percent of young adults own a smartphone and 17 percent rely on their smartphone as their primary access to the internet. While the tool looks OK on mobile devices, users still need to navigate to the tool through their device’s browser. With no dedicated mobile app, it’s no surprise the researchers had trouble getting students to use the tool. Also, search engine’s are often people’s first stop on the internet, not specific sites. That’s why we’ve been working with tech companies like Google to incorporate better college info into search results. It’s very important to meet users where they are, rather than start from scratch.

Ed is a People Business

As mentioned above, the researchers worked with high schools to promote the tool through flyers, posters, trainings, and other communications and outreach efforts. It’s unclear however how much the high schools really integrated the tool into their existing programs and curricula, and included outreach to families and community organizations. The researchers provided “postcards, posters, pens, sunglasses, backpacks, and water bottles branded with the GradpathVA URL and logo.” But given young adults’ skepticism of being marketed to, these efforts easily could have backfired, and young people turned away by assuming GradpathVA was just another for-profit company vying for their finite dollars and attention.

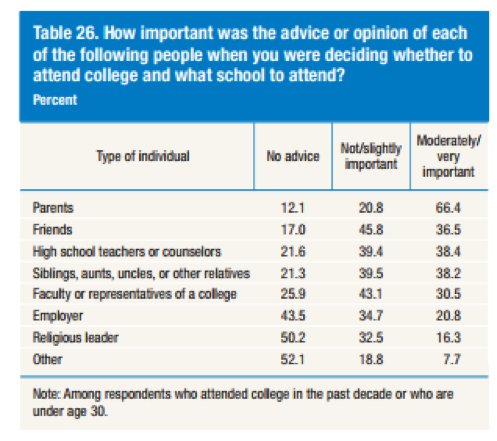

Also, in our experience, no search tool can replace the the personal connections of a trusted family friend or relative. The Federal Reserve’s Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking recently found students value advice from family, teachers, and counselors the most when making college decisions. Successful tools need to earn buy-in from all these figures.

Measuring the tool’s influence

The other bucket of the study’s problems is how the researcher’s defined the tools’ effects: whether students chose majors with high earnings potential and whether that choice changed from their previous preference, each compared between a control and a treatment group who received different versions of the tool. As mentioned above, students didn’t really use either tool, so right off the bat they don’t have much to compare between. But let’s address each of these effects.

Students go to college for better jobs (but other reasons too)

To suggest that all students pursue postsecondary education solely for economic success, and thus would make rational choices to improve their economic prospects, is a simplification of student motivations. It’s true polling consistently finds economic motivations at the top of student priorities, but other factors play in as well: Learning more about a given subject, expanding social and professional networks, and becoming a better person, were recently cited by a majority of students as reasons to pursue college. These factors play into student decisions of where to enroll and what to study, and weren’t accounted for in this study.

Problematic Baseline

To determine whether labor market information changed students’ decisions on what to major in, the researchers compared what major students selected when taking their PSAT, a standardized test taken by sophomores and juniors and determined whether their new choice had higher projected earnings. First of all, the PSAT major choice takes place years before a student actually declares a major. It’s normal for student interests to shift for all sorts of reasons, and assuming that a website (again, that no one really used) would have exclusive impact on choice is methodologically unsound.

Secondly, selecting what major you are interested in is voluntary on the PSAT. That’s why we shouldn’t be surprised that only a third of students the researchers looked at declared a major on their PSAT and in their current enrollment, complicating the comparison (p 19).

Conclusion

The researchers should be commended for taking on such a complex and important topic as college choice, and the flaws of their study are not unique to their project. As the researchers themselves acknowledge: “Successfully placing new information in the hands of high school students requires obtaining buy-in from schools, students, and families. We suspect that the challenges we faced were not unique to our study, and that other efforts to inject more information into the market for higher education are likely to face similar changes.” But just because providing good information and improving decisions is hard, doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try.

The authors are also right in their recommendations to incorporate any new tool into existing curricula, for state and federal governments to continue to collect outcomes information for transparency and accountability purposes, and to improve design and communication of college information. Unfortunately, the researchers may not recognize the unintended consequences of their study; taken out of context, opponents to equipping students (and policymakers) with valuable information could point to this study as evidence that information doesn’t matter, and we should continue to operate in a dark but noisy information landscape.