By Eric VanDreason

This time of year in Washington is known as “merry-go-round” season. With a new Congress and unofficial presidential campaigns shaping up, many Millennials in government or politics are likely to switch jobs.

Pundits have been quick to peg our generation as one of job-hoppers. But research shows that our peers don’t suffer from commitment-phobia. It’s recently been suggested that the separation rate (the rate at which employees leave their employers) for young people is hardly different today than it was in the 1970s or 1980s. Rather, the likelihood is higher for today’s younger generation to make a career change — a subtle, but important, distinction.

This phenomenon has to do with the significance of what has been called the “dream job premium.” As Derek Thompson recently wrote, “Jumping between jobs in your 20s, which strikes many people as wayward and noncommittal, improves the chance that you’ll find more satisfying—and higher paying—work in your 30s and 40s” because it’s a method young people have used to find their “true calling,” or work that better suits their personal interests. It’s also been shown to improve raises, as those staying employed at the same company for over two years on average will earn half as much over their lifetime.

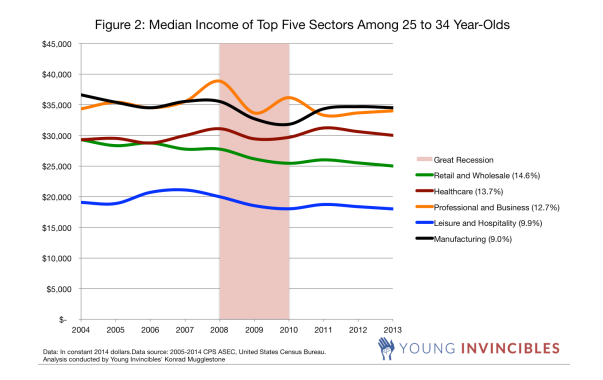

Even as job-hopping makes financial sense for Millennials, the Great Recession has actually caused many to stick with their jobs longer than their counterparts a decade ago. The median length of job tenure for 25-34 year olds was 3.2 years in 2012, up from 2.7 years in 2002. Despite being more educated than previous generations, the decline and/or stagnation of median wages in the industries most likely to be hire Millennials means they run the risk of being worse off financially than their parents were.

When employers cite this pattern as a reason to hold back investing in young workers, it perpetuates a vicious cycle: Employers hesitate to train young workers because they might leave, giving those workers the impetus to leave and gain the skills that will allow them to advance in their careers elsewhere.

Young workers desire to have opportunities for growth within one workplace, but staying put necessitates flexibility and a commitment of time on the part of the employer. That may mean a leadership development program for recent graduates, or something akin to what LinkedIn Co-Founder Reid Hoffman and Do Something CEO Nancy Lublin described as “tours of duty,” a flexible, transparent, highly personalized mutual commitment by both employer and employee to complete a significant but clearly defined set of goals over a finite amount of time.

Yet these scenarios present an ideal that isn’t common across the current landscape of work available to young people. Instead, Millennial workers are forced to create their own leadership development on-ramp to broader opportunities, and job-hopping is often pointed to as a means to do so.

We’ve seen the devastating impact the Great Recession has had on young adults, from declining wages to higher rates of unemployment. Many college graduates preparing to enter the workforce say they are willing to take a pay cut to obtain a job where they can make an impact. If employers show a commitment to their Millennial employees through long-term investment and give them opportunities for growth and meaningful contribution, their desire to acquire and retain young talent may not be so far out of reach.